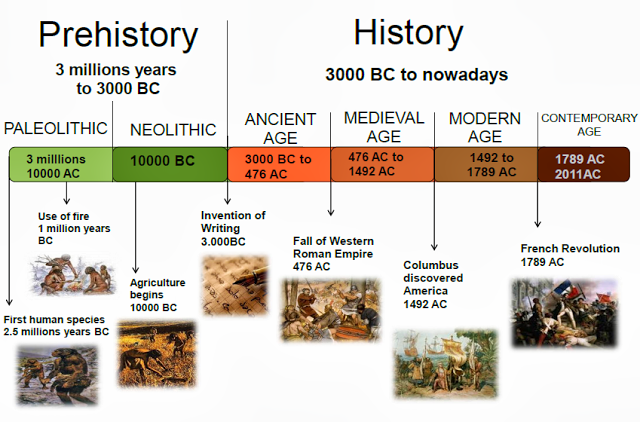

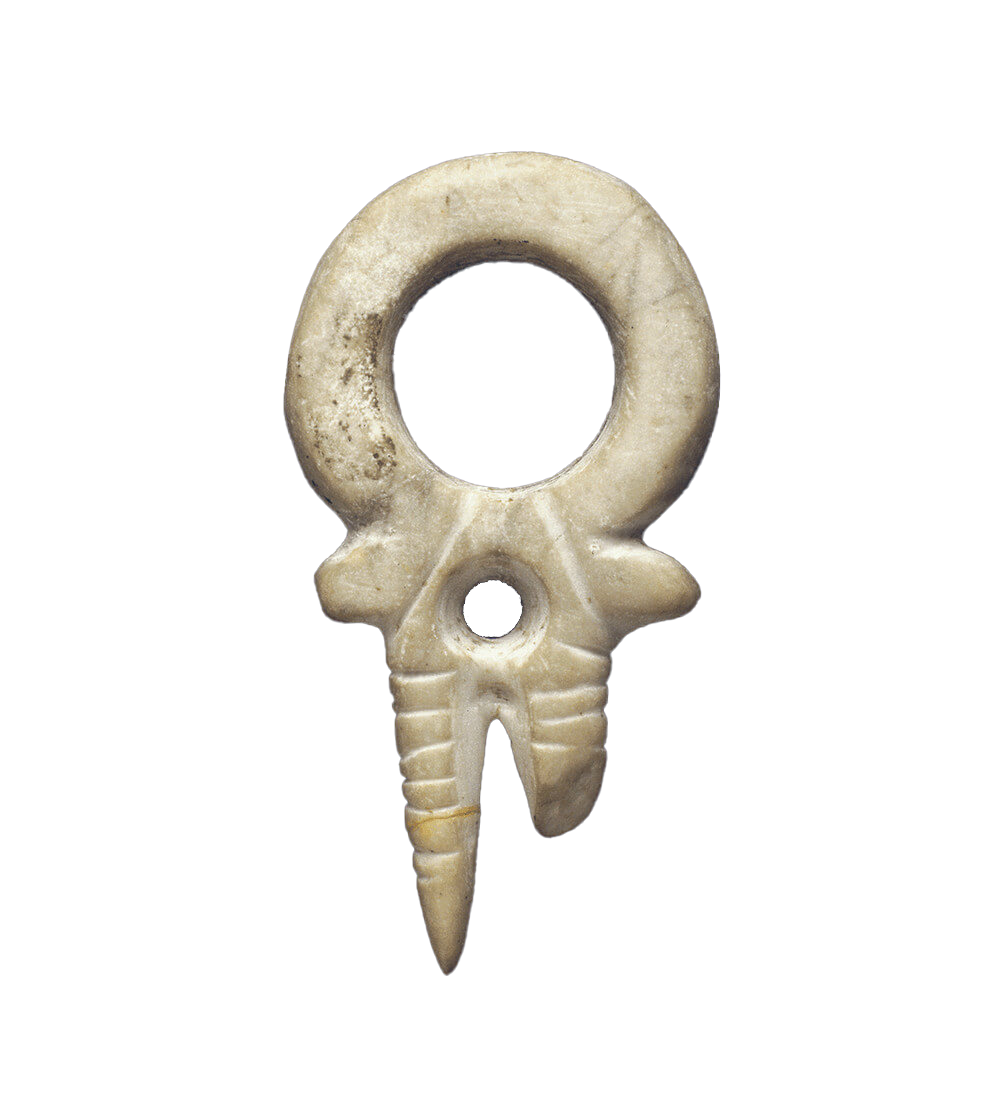

Lepenski

Vir

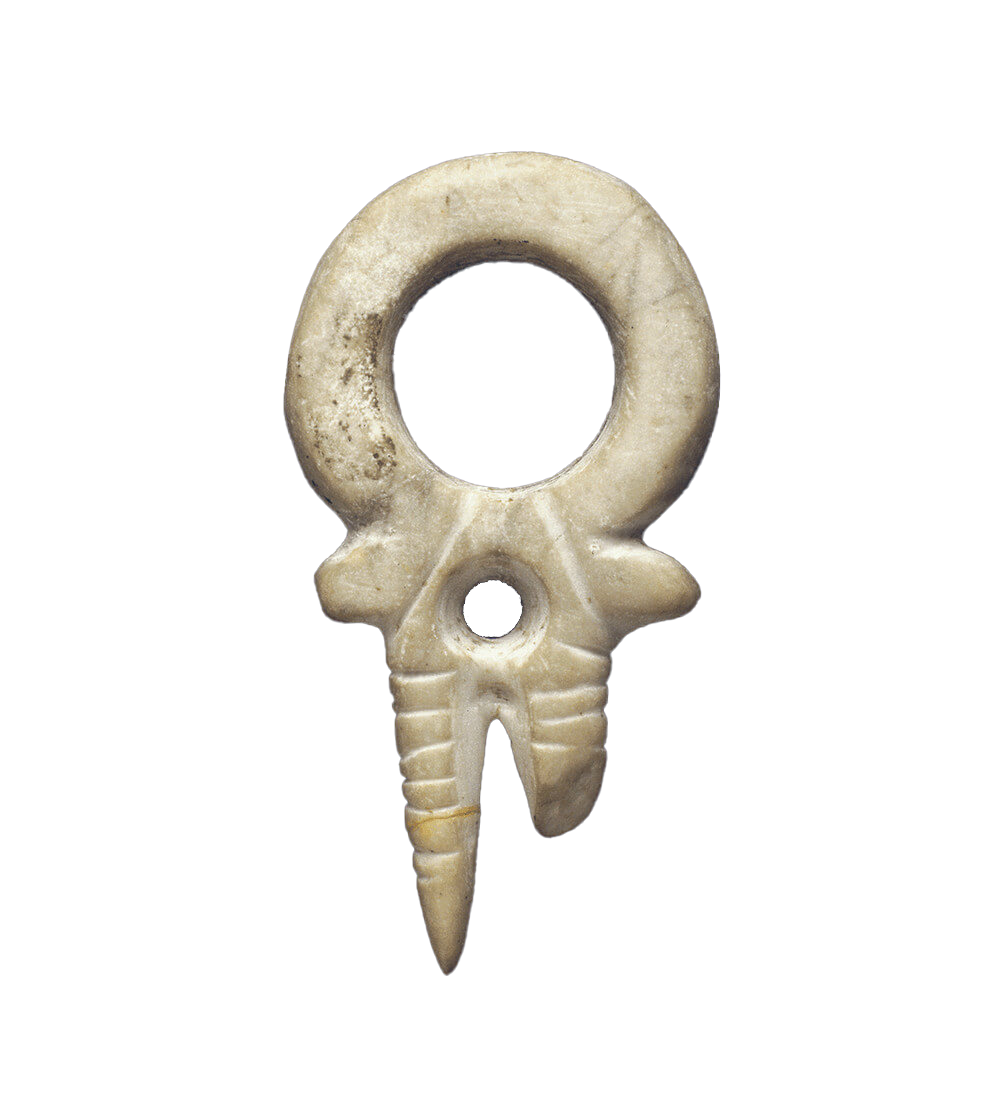

Amulet carved from animal bone, Lepenski Vir

|

Period: 9500-6000. BCE

Findings: Trapezoidal houses, fish-human stone sculptures

Significance: One of the earliest permanent settlements in Europe

|

|

|

Vinča

%20-%20(MeisterDrucke-85901).png)

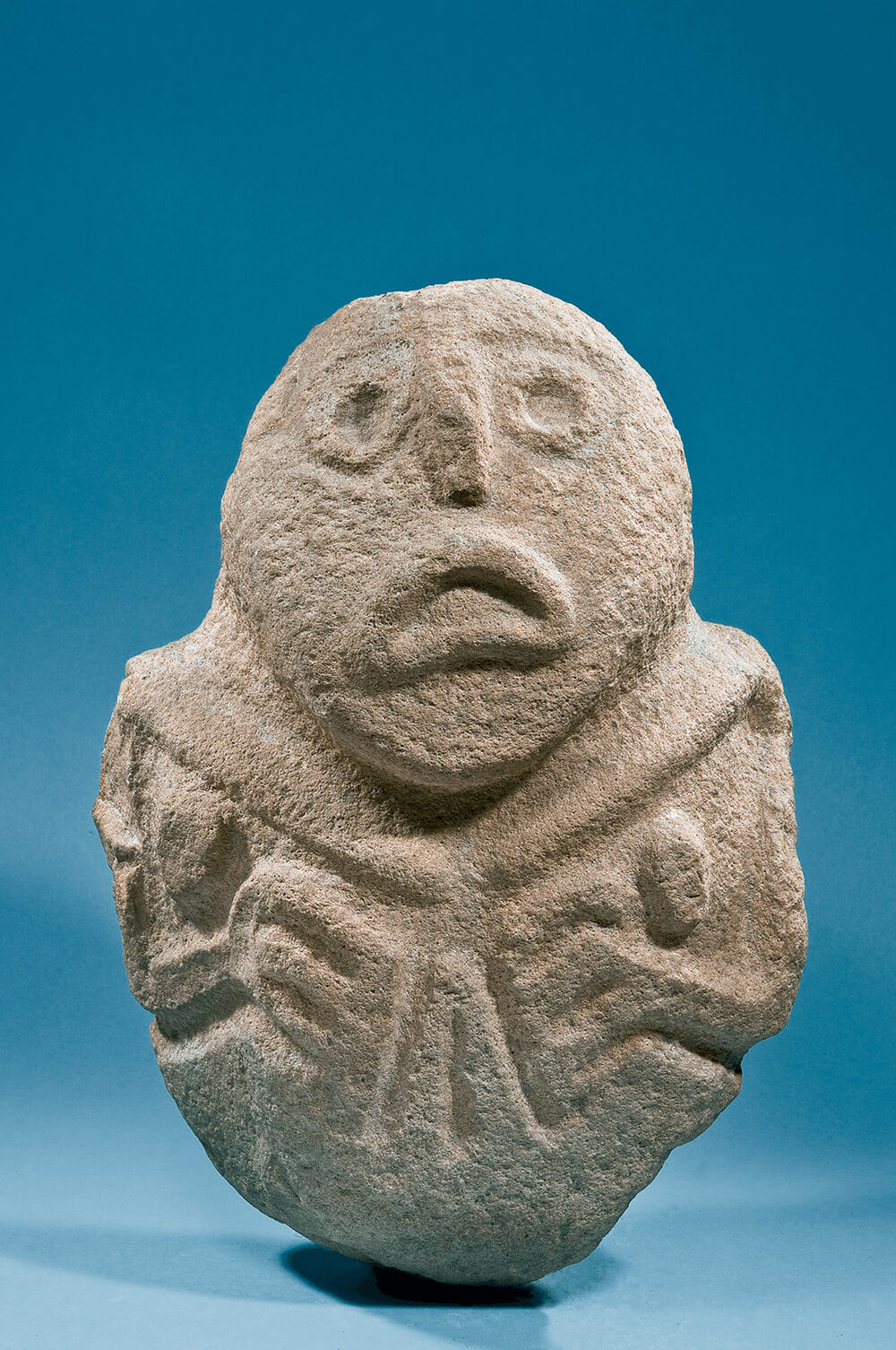

Stylizied head from clay, Vinča culture

|

Period: 5400-4500. BCE

Findings: Pottery, figurines, proto-symbols, copper smelting

Significance: Large Neolithic proto-urban settlement; possible

proto-writing system

|

|

|

Singidunum

later

Belgrade

Roman ring from Singidunum, gold with blue gemstone

Belt-buckle from Singidunum, gold plated bronze with almandines, 5th

century

Belgrade castle from the time of Despot Stefan, 15th century

|

Period: From Paleolithic to Iron Age

Findings: Early habitation layers (Starčevo, Vinča, Bronze and Iron Age)

Special note: In 1938., mammoth remains were discovered during construction of the "Albanija" Palace, becoming part of urban legend. Later bridge works over the Sava and Danube revealed large quantities of mammoth bones and tusks, showing that beneath modern Belgrade lies a prehistoric “cemetery” of Ice Age animals.

Significance: Continuous settlement before Roman fortifications.

|

Preroman (800-75. BCE): Thracians, Dacians, Celtic Scordisci founded

Singidunum

Findings: Settlement layers, Scordisci oppidum

Significance: Early habitation before Roman fortifications

Roman Period (1st-7th century): Roman fortifications, legionary camp; Byzantine and Slavic layers

Findings: Castrum, military architecture, urban remains

Significance: Important military stronghold on the Danube frontier

|

Period: 12th-15th century

Findings: Medieval walls, towers

Significance: Key defensive stronghold at Sava-Danube confluence

|

Viminacium

"Mona Lisa" from Viminacium, 4th century frescoe

|

Period: Neolithic-Bronze Age

Findings: Mammoth remains, prehistoric settlement layers

Significance: Evidence of long settlement continuity before Roman period

|

Period: 1st-7th century

Findings: Amphitheater, baths, necropolis; cemeteries and burials of Goths, Huns, Slavs

Significance: Major Roman military camp and city; destroyed during invasions but life continued through Migration burials

|

|

Felix Romuliana

(Gamzigrad)

Roman mosaic depicting Dionysus, Felix Romuliana (Gamzigrad), 3rd-4th century

|

|

Period: 3rd-4th century

Findings: Palaces, temples, mosaics

Significance: Imperial complex of Emperor Galerius, UNESCO site

|

|

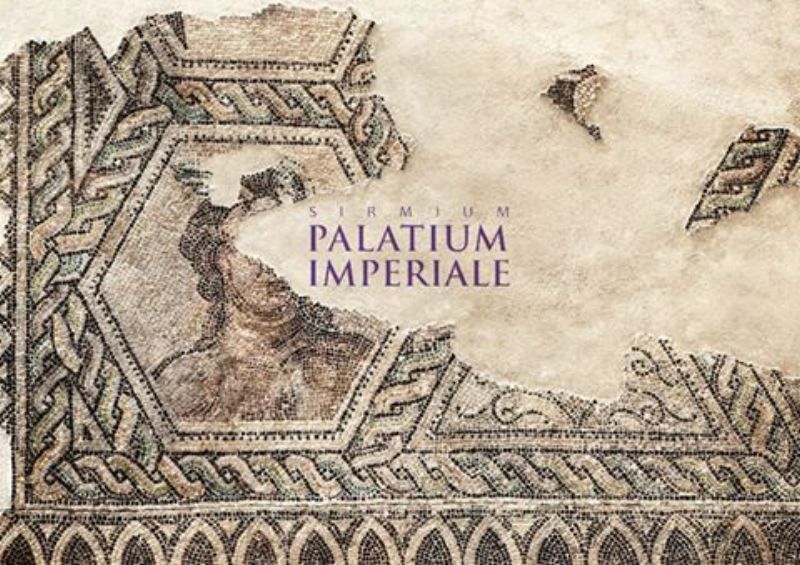

Sirmium

Roman marble sculpture, head of Venus, Sirmium, 1st century AD

|

|

Period: 1st-6th century

Findings: Palaces, coins, basilicas; Christian basilicas, ruins after invasions

Significance: One of the capitals of the Roman Empire; repeatedly destroyed during Gothic and Hun invasions

|

|

Naissus

(Niš)

and

Mediana

Roman bronze sculpture - head of Constantine the Great, Naissus, 4th century

|

|

Period: 3rd-6th century

Findings: Fortifications, baths, basilicas, mosaics, sculptures; ruins after invasions, traces of Gothic and Hun destruction

Significance: Birthplace of Constantine the Great; key city in Migration era, devastated but remained strategic

|

|

Justiniana Prima (Caričin Grad)

Golden coin of Justinian I, Justiniana Prima, 6th century

|

|

Period: 6th century

Findings: City walls, churches, administrative buildings

Significance: Founded by Emperor Justinian I

|

|

Gradina na

Jelici

Bronze bells, Gradina na Jelici, 6th-7th century

|

|

Period: 6th-7th century

Findings: Jewelry, ceramics, liturgical objects, five churches, frescoes, graves inside churches, fortifications

Significance: Byzantine fortified highland city during late Antiquity and the Migration Period

|

Period: 7th-9th century CE

Findings: (to be added)

Significance: Early Medieval continuation: 8th-9th century - small fortified Slavic settlement.

|

Studenica Monastery

Medieval Serbian tableware, enameled and painted terracota, Studenica monastery, 14th-15th century

|

|

|

Period: 12th century

Findings: Churches, frescoes, relics

Significance: Most important Serbian monastery, UNESCO site

|

Gračanica Monastery

Frescoe depicting queen Simonida, Gračanica monastery, 14th century

|

|

|

Period: 14th century

Findings: Church, frescoes

Significance: Masterpiece of Serbian medieval architecture, UNESCO site

|

Golubac Fortress

Golubac fortress, 14th century

|

|

|

Period: 14th century

Findings: Towers, walls, gates

Significance: Strategic fortress on the Danube

|

Smederevo

Fortress

Smederevo fortress with palace, 14th century

|

|

|

Period: 15th century

Findings: Walls, towers, citadel, ceramics, jewlry, weapons, everyday objects

Significance: Largest medieval fortress in the Balkans

|

Novo Brdo

Serbian medieval jewlry, discovered at Novo Brdo fortress, 14th-15th century

|

|

|

Period: 14th-15th century (conquered in 1455.)

Findings: Fortress, remains of churches, mining equipment, jewelry, coins

Significance: Major medieval mining (silver & gold) and trade centre; economic hub of the Serbian Despotate; site of the Mining Code (Zakonik o rudnicima)

|

Resava (Manasija Monastery)

Resava monastery, 15th century

|

|

|

Period: 15th century

Findings: Church, frescoes, fortified walls

Significance: Founded by Despot Stefan Lazarević; Morava architectural school; cultural and literary center

|

%20-%20(MeisterDrucke-85901).png)